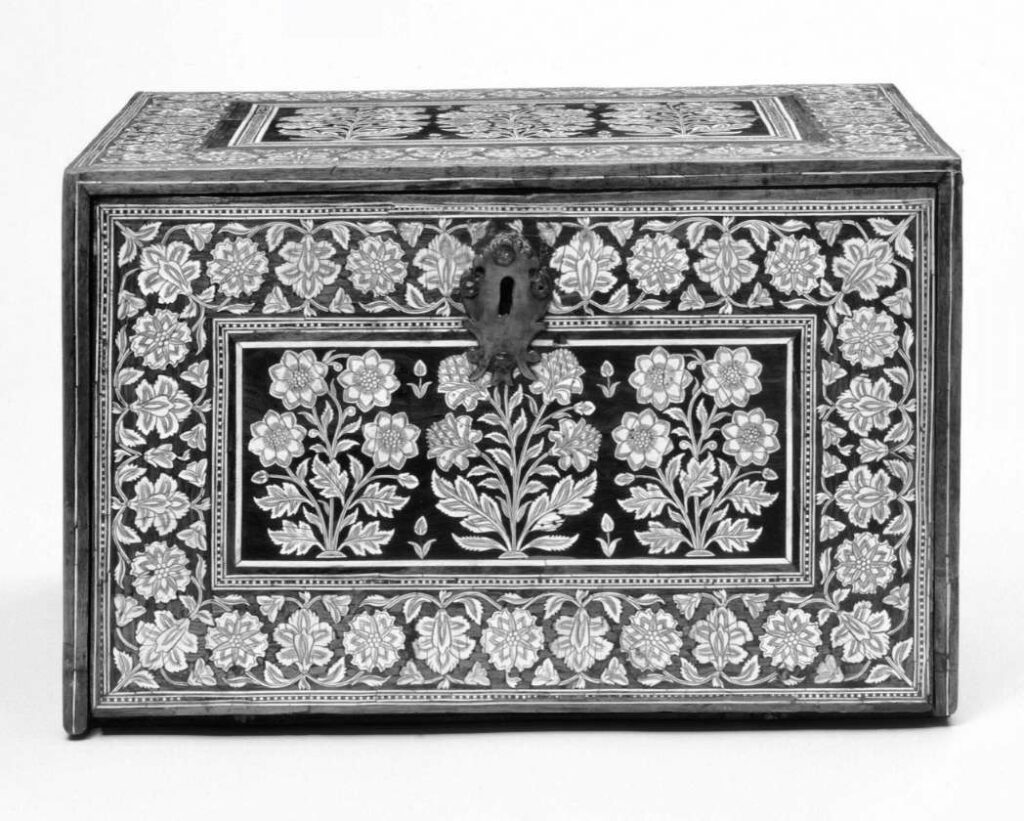

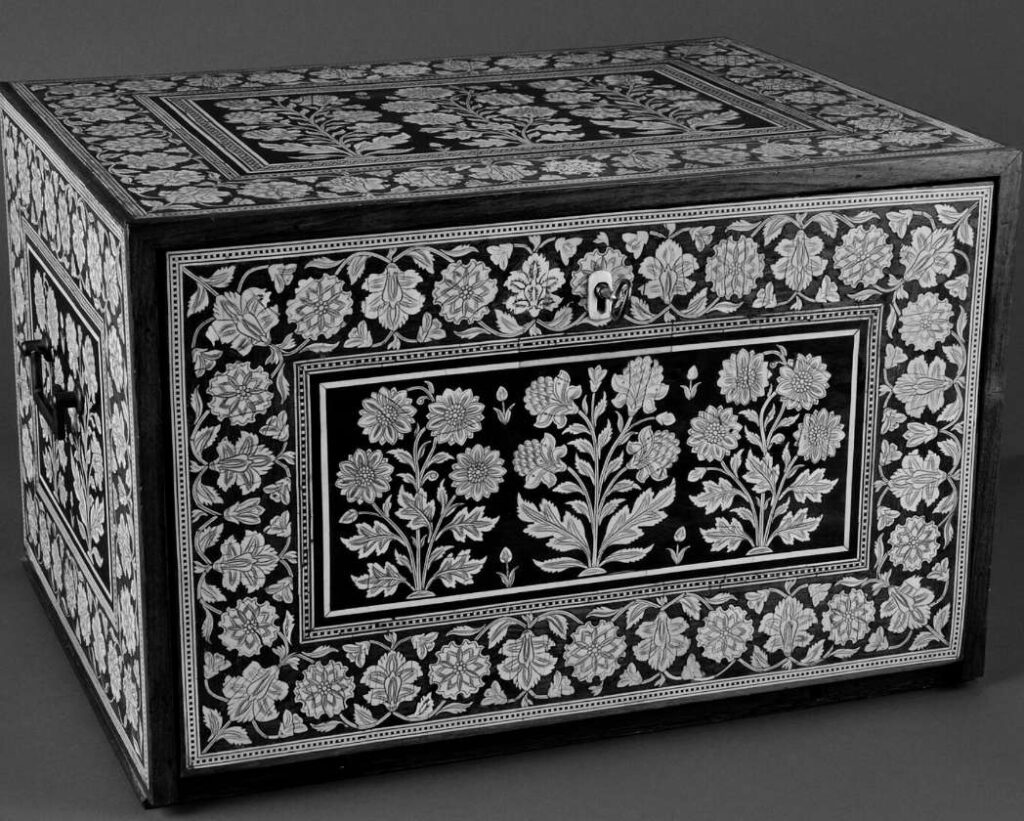

Of rectangular form with fall-front opening profusely decorated in ivory inlay; sides with rectangular panels containing large inlaid ivory flowers within two border engraved with floral design; the front panel containing three large floral sprays surrounded by a double engraved border opening down to reveal eight drawers. This is a box that opens at the front to become a writing surface but also serving as a coffer in which to keep small precious objects such as jewelry or relics.

Produced in the north of India, in the region of the Great Mughal, this writing box adheres to a formal structure very close to that of European models.

While in India the colonial powers discovered, to their surprise, rare articles of courtly furniture richly worked and inlaid. However there was no local furniture that suited the settlers manner of living, so they commissioned extravagant pieces along European lines from native craftsmen, allowing them free rein with local materials.

Fall front cabinets such as this were designed to satisfy the demand of the settlers and many similar cabinets entered the collections of European aristocratic houses in the 17th and 18th centuries but they were also adopted by Indians, as seen in a Shah Jahan period miniature illustrated in Luxury Goods from India, the art of the cabinet maker, Amin Jaffer, 2002, p. 18.

This monumental fall-front cabinet was designed with an outstanding array of floral details. The popularity of flower studies in early seventeenth century Indian art followed on from a long-standing Mughal appreciation for flowers that since the days of Akbar had manifested itself in courtly painting and decorative arts but It was under Shah Jahan (r. 1628-58) however that the use of floral motifs were treated not as secondary decorative elements, but the primary focus of decoration. Jahangir’s well-documented interest in flowers gave an added impetus to a group of artists and patrons already interested both in natural history and naturalism in painting. This is evident in the careful rendition of the floral stems on this example.

During Shah Jahan reign, similar floral motifs to those seen on our cabinet were found on a wide variety of media – such as the decoration of buildings erected by the Emperor, for exemple the Saman Burj, Agra Fort (ca. 1637) or the Diwan-i ‘Amm in Ajmer as depicted in the Padshahnama (Milo Cleveland Beach and Ebba Koch, King of the World. The Padshahnama, exhibition catalogue, London, 1997, no.5, pp.28-29). By the second half of the 17th century similar motifs were popular also for cabinets (Basil Gray (ed.), The Arts of India, Oxford, 1981, p.180).

The resulting fusion of Western forms with Indian materials and decorative techniques gave rise to a wide range of luxury goods – cabinets, game-tables, painted boxes, ceremonial arms – that were breathtaking in their craftsmanship and widely prized in Europe.

With their intellectual curiosity and cultural policies, the Mughals were able to create a space of tolerance and harmonisation of different cultures.

This kind of cabinet illustrate the subtle interaction between European and Indian tastes and sensibilities, and chart the course of colonial patronage.

Bibliography:

- Milo Cleveland Beach and Ebba Koch, King of the World. The Padshahnama, exhibition catalogue, London, 1997

- Basil Gray (ed.), The Arts of India, Oxford, 1981

- A. Jaffer, Luxury Goods from India: The Art of the Indian Cabinet-Maker, Victoria and Albert Museum, 2002

- Brend in Arts of Mughal India : Studies in honour of Robert Skelton, ed. A. Topsfield, R. Crill, S. Stronge, London, 2004