Exhibitions :

– Il tesoro d’Italia, a cura di Vittorio Sgarbi, Expo 2015, 22 maggio-31 ottobre 2015, Silvana Editoriale, pp. 162-163, Emilia n. 4

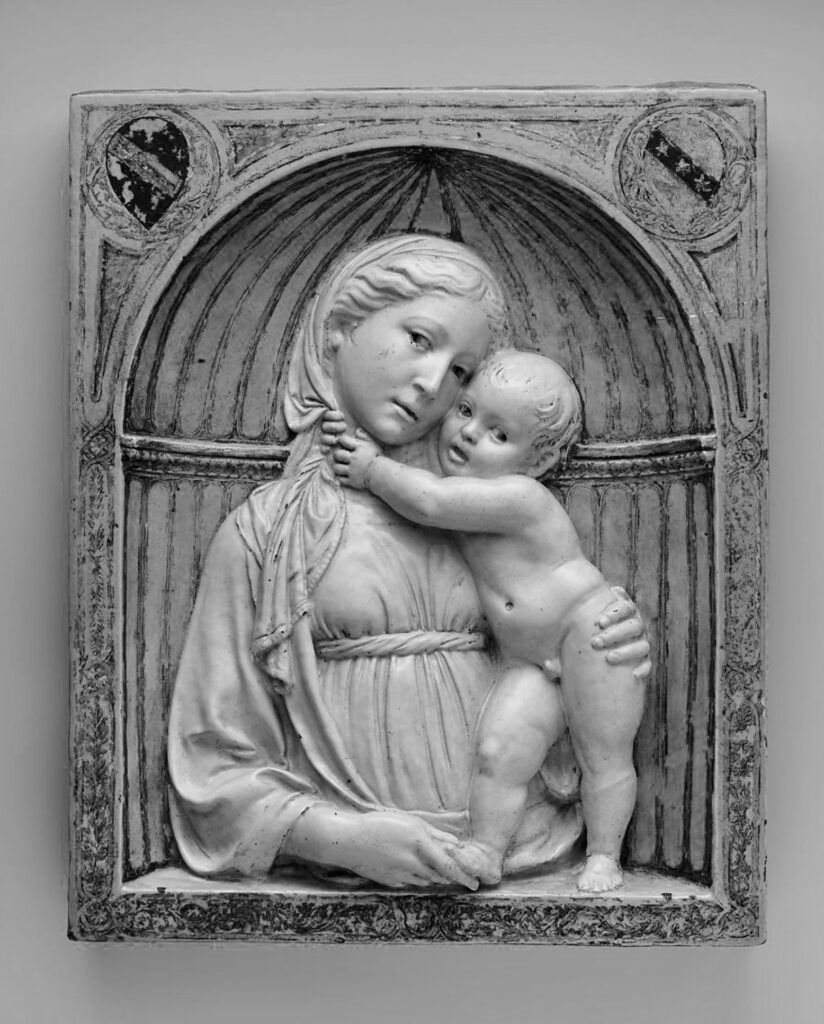

Modeled in half-length, The virgin, tenderly holding her Son, raise from an angel’s head, against a blue starry background.

The Child is clutching his mother’s veil with one hand, his other at her back. The Mary’s thick mantle and robe and lighter veil envelop her and offer protection to the Child, who entwines the veil with his hands.

This Madonna is portrayed with pleasing, youthful features; she tenderly support the Child Jesus and lightly cradles His foot which she holds between two fingers; a graceful, touching iconographic invention.

The artist was clearly interested in a naturalistic rendering of the subject as seen in the painted details of the hair and faces and the careful modeling of the drapery.

The outstanding original fifteenth-century polychrome rendition is the most fascinating element of this haut-relief in stucco. The highly refined painterly details are rendered with touching graphic skill, as in the facial features and in the refined decoration of the Virgin’s veil and the clothes of the Child as in the angel’s wings.

This elegant relief is quintessential example of works that Renaissance Italian artists produced for domestic devotion.

So popular were images of the Madonna and Child that artists sought to vary and polish their composition. It is a forceful representation of the subject, but two very different qualities, intimacy and modest scale, are what make this kind of relief so successful.

This stucco shows an intimate and beautiful composition, a peculiar domestic feel, an appealing naturalism that suggest it was inspired by an illustrious model; the mastery of the technique indicate an artist familiar with the refined elegance of Tuscans workshops.

The iconography of the Madonna holding Christ’s foot and of Christ grasping his mother’s veil, popular in Renaissance Italian panel painting as well as sculpture, derives from Byzantine icons. But it appears that Luca della Robbia have first essayed the half-length Madonna holding a Child in a work in stucco (Musée Jacquemart-André, Paris) about 1430.

With regard to the molding, as Enzo Carli pointed out, it is of a model retraceable to a well-known typology, diffused through numerous replicas made both by the master himself and others, of the Corsini Madonna by Luca della Robbia, dateable to the fifth or sixth decade of the fifteenth century.

Especially the impetus and quick manners of the Child, that bear witness to the as yet fresh experiences of Masaccio and Donatello, confirms that this stucco may be inspired by Luca Della Robbia prototype.

This high relief was first examined by the Professor Giancarlo Gentilini in 2008 who attributed it to a « collaborator or follower of Luca della Robbia (Madonna del tipo Corsini) c. 1450-60. Perhaps Ferrara, Antonio di Cristoforo » cit. (« collaboratore o seguace di Luca della Robbia (Madonna del tipo Corsini) 1450-60 ca. Forse Ferrara, Antonio di Cristoforo »).

As Gentilini explains (op.cit.), the majority of Luca’s sculptures from his early years were pigmented with natural tints and it is only after the 1440s that he is consumed with producing glazed terracotta sculptures.

The back of this stucco is solid and flat as the Friedrichstein Virgin, cast from the same mold, of the Virgin and Child in a Niche, of the type known as the “Bliss Madonna”: these are in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York and in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and are also datable to the same period.

Luca della Robbia, The Bliss Madonna, Met, New York

The Buffalo Virgin, which is distinguished by more detailed modeling, more accurate technical execution (see, for example, the way that the back of the panel is finished with chamfered edges to the borders) and a more delicate palette in the glazing, could be an entirely autograph work (its high quality and its claim to this status has been endorsed by Avery 1976 and Pope-Hennessy 1980, after seeing it with their own eyes in April 1976), while the Berlin version could be a replica delegated to an assistant – such as Luca’s young nephew Andrea della Robbia (Florence 1435 – 1525), who was documented as working in Luca’s studio from 1451 onwards. Alternatively, acknowledging the initial experimental phase of Della Robbian art, it might be that the Buffalo Virgin was executed by Luca some time later, with a perfected technique and revisions to some of the details of the modelling. However, it is not impossible that different destinations may have accounted for such variations.

Nevertheless, there can be no doubt about Luca’s responsibility for this touching model, which clearly demonstrates the “familiar, pleasing, but suspended and silent humanity” that distinguishes the master’s best work towards the middle of the century.

« L’accentuata toscanità » (The accentuated Tuscan character) of our stucco relief indicate that the author was familiar with the iconographical innovations proposed in Florence; meanwhile this stucco shows some significant affinities, especially in the polychromy, with the refined artistic atmosphere of the este court.

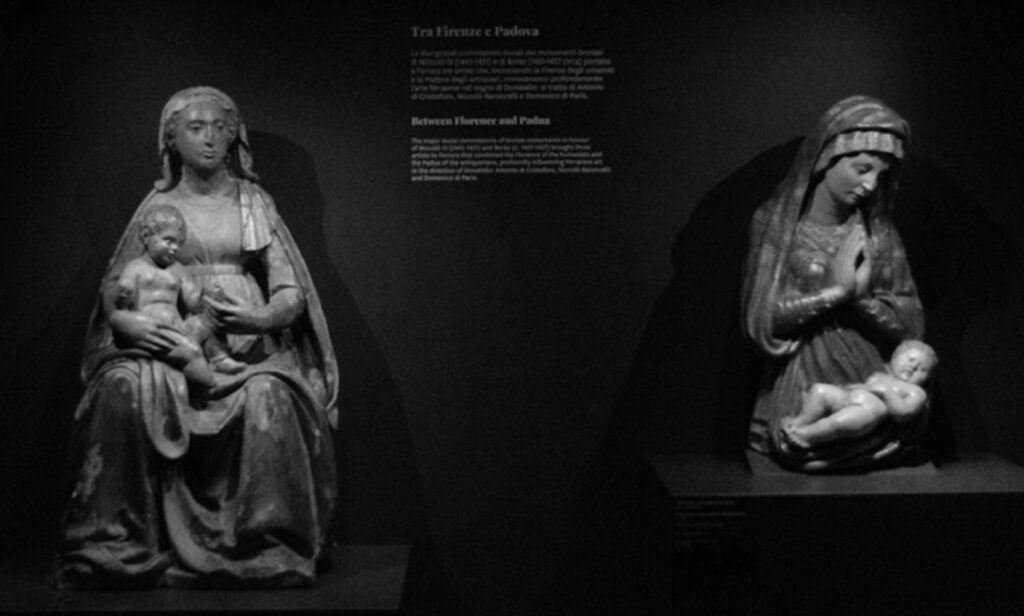

Palazzo Schifanoia, Ferrara. Sculptures attributes to Antonio di Cristoforo, Niccoló Baroncelli and Domenico di Paris

As Giancarlo Gentilini first suggested this work could be by the hand of an artist active in Ferrara as Antonio di Cristoforo (Gentilini, 2008). In fact The centres north of the Arno, in which plastic art were practiced, were Bologna and Padua, the latter being the town in which Donatello, during a sojourn lasting over ten years, succeeded in firmly establishing the tradition of the Florentines. The restricted circle of pupils and other collaborators adapted Donatello’s style in a more or less successful personal manner, and so established it in many provinces, both in the immediate neighborhood of Padua and further afield. Ferrara, a close neighbor of Padua, naturally could not remain independent of the effect of the great Florentine’s long years of work in the vicinity. Although very few sculptures dating from the first decades of the century have been brought to light in the city of Este, too few to give any clear impression of the existence of a native school of carvers, from the beginning of the ‘forties we are confronted with one tangible personality bearing the name of Niccoló Baroncelli. This artist was a native of Florence and, according to Vasari, had been a pupil of Brunelleschi. His existing works indicate a long apprenticeship with Donatello.

Baroncelli, who, through his engagement in the service of the Estensian Court, remained in Ferrara till his death in 1453, must have been an active worker, but unfortunately, the greater part of his work has been lost. We found evidence in them of the extent to which his gifted pupil and son-in-law, Domenico di Paris, a Padouan by birth, obtained his artistic education from him. Domenico, documente as « maestro de figure de terra et de metallo » (maître des sculptures en terre-cuite et métal) played a leading part in Ferrarese sculpture during the second half of 15th century. Born in Monselice, he was formed in Padua, where he familiarized with the works of Donatello. Around 1442 Domenico di Paris is documented In Ferrara, together with his brother in law, the Florentine sculptor Niccoló Baroncelli who had been invited to the city to create the equestrian monument of Borso d’Este (destroyed in 1796) and a set of five bronze sculptures for the cathedral. After Baroncelli’s death in 1453, Domenico completed all the commissions. In 1467 Domenico was engaged as « intarsiator lignaminis » in the execution of the ceiling of the « Camera Superioris » of palazzo Schifanoia.

Domenico di Paris, temperantia, relief en stuc, Palazzo Schifanoia, Ferrara

The major ducal commissions of bronze monuments in honor of Niccoló III (1443-1451) and Corso (1451_1457) brought three artists to Ferrara that « combined the Florence of the humanists and the Padua of the antiquarians, profoundly influencing Ferrarese art in the direction of Donatello: Antonio di Cristoforo, Niccoló Baroncelli and Domenico di Paris » (cit. permanent exhibition in the recently re-opened Palazzo Schifanoia, 2020).

In the present relief representing the Virgin and the Child, the influence of the Paduan works of Donatello is filtered by a softer vision partly indebted to Florentine models; the style is far from the expressionist irregularities of his contemporaries working in Ferrara.

A very similar relief from the Dogliani Collection, of inferior quality, show the same composition of our relief. Dated 1480, this timeline is indicative of the production of our stucco as well.

The decorative finesse, the richness of the polychrome and the naturalistic attention of this Virgin and The Child show affinities with the Virtues of the Stucco room in Schifanoia, last documented work of Domenico di Paris.

The accentuated tuscan character and the stylistic affinities with the reliefs in Palazzo Schifanoia, as also the remarkable similarities with some sculptures attributed to Baroncelli, led the art historian Paola Ranzolin to attribute this work to Domenico di Paris and to publish it in the exhibition curated by Vittorio Sgarbi in 2015 (International expo – « Il Tesoro d’Italia ») where a selection of treasures of the Italian artistic patrimoine were presented according to a regional approach aimed to enhancing the richness and individuality of the different provinces of the Peninsula. This stucco is one of the 27 works selected to represent the evolution of the rich artistic heritage of Emilia Romagna.

Bibliographie:

- Il tesoro d’Italia, a cura di Vittorio Sgarbi, Expo 2015, 22 maggio-31 ottobre 2015, Silvana Editoriale, pp. 162-163, Emilia n. 4

- Enzo Carli, Urbano da Cortona e Dontaello a Siena, in Donatello e il suo tempo. Atti del convegno 25 sett.-1 ott. 1966, Firenze-Padova. Firenze, Instituto Nazionale di Studi sul rinascimento, 1968

- David J. Drogin, Patronage and Italian Renaissance sculpture, routledge, 2016

- Dussler, L. (1926). An Unknown Sculpture by Domenico di Paris. The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, 48 (279), 301–303

- G. Gentilini, I Della Robbia : la scultura invetriata nel Rinascimento, Florence, 1992, vol. 1, p.48.

- G. Gentilini, communication écrite sur l’oeuvre, 13/02/2008

- Abigail Hykin, “Materials and Techniques,” in Della Robbia. Sculpting with Color in Renaissance Florence, ed. M. Cambareri, exhibition catalogue, Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, 9 August – 4 December 2016, Washington, National Gallery of Art, 5 February – 4 June 2017, Boston 2016, pp. 128-143, 154-156

- Allan Marquand, Luca della Robbia, Princeton, 1914, no. 88.

- Adriano Peroni, Pavia, Musei Civici del Castello Visconteo, 1975 Calderini

- John Pope-Hennessy, Luca della Robbia, Ithaca, 1980, p. 251.

- M. Reymond, “La Madone Corsini de Luca della Robbia,” in Rivista d’Arte, II, 1904, pp. 93-100.