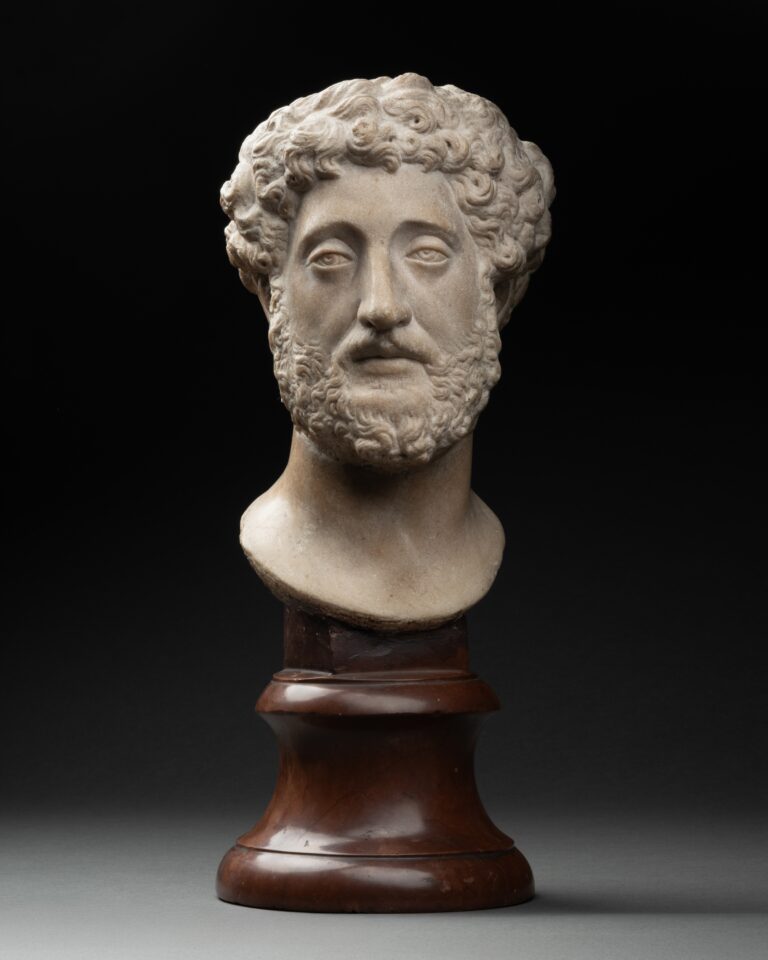

Exquisitely carved, this relief portrays a winged cherub with cascading hair and delicate features. The cherub’s plump, smooth countenance, rounded cheeks, outlined lips, and finely drawn nose emanate a sense of tenderness. The quadrangular module, is adorned with a carved frame. The relief ascends gradually, transitioning from the low relief of the wings to the high relief of the head.

The rectangular frame and the subtly curved form of the artwork suggest that the relief likely adorned the upper part of an arch or a vaulted chapel. The type is that of the perspective room with a coffered ceiling decorated with figures of winged cherubs, which is found in various Neapolitan chapels of the 15th century. Coffered ceilings attest to the recovery of antiquity and the search for luxury in Renaissance architecture, first in Florence, then in Rome and Naples. The majority of the numerous family chapels and tombs built during the late fifteenth century in South of Italy employ the new formal vocabulary of the Florentine Renaissance in a self-confident manner that permitted a broad spectrum of variations.

The escalating admiration for the classical world, coupled with the development of perspective, significantly contributed to the Renaissance endorsement of coffered ceilings. This artistic and constructive device drew inspiration from the intricate marble patterns observed in historical landmarks such as the Arch of Titus, the Temple of Vesta in Tivoli, the Pantheon, and the Basilica of Maxentius. A distilled product of both mathematical and artistic cultures, deeply scrutinizing the ancient world, the coffered ceiling plays a vital role in the perspective construction of space with its regular and directional geometry. The motif of the coffered ceiling decorated with cherubs in relief was introduced in Naples by Francesco Laurana in the plastic decoration of the Arch of Castelnuovo. Laurana’s impact on the art scene in the south of Italy was profound. The introduction of the winged cherub into the region’s artistic vocabulary bridged the gap between the classical and the contemporary, creating a synthesis that resonated with both aesthetic and spiritual sensibilities. His influence extended beyond the immediate visual appeal, shaping the cultural identity of the Renaissance in southern Italy. Although the plastic decoration of the Arch of Castelnuovo cannot certainly be ascribed to a mature Renaissance style, it was precisely on this occasion that the sculptors who worked there could get to know and export throughout the Italian peninsula that type of “Florentine classicism” which, even in the 15th century Naples, was conditioned by the Burgundian culture imported into the Kingdom by Alfonso of Aragon himself, with artists called from Spain and Northern Europe. The coffered ceiling, with its geometric patterns and Laurana’s winged cherubs nestled within, became a symbol of refinement and cultural sophistication. The relief sculptures, carefully integrated into the overall design, transformed the ceiling into a celestial realm, inviting viewers to contemplate the divine while immersed in the grandeur of the Renaissance space.

Similar winged cherubs appears also in the Naples cathedral. Within the renowned Succorpo Chapel, a mesmerizing marble coffered ceiling adorned with cherubs epitomizes the splendor of the Neapolitan Renaissance. The interplay of light and shadow on the textured surface of the marble coffered ceiling introduces an ethereal dimension, providing an immersive visual experience for observers. The geometric precision and the repeated patterns, reminiscent of classical motifs, establish a sense of harmony and balance that has become the hallmark of the Neapolitan interpretation of Florentine Renaissance.

Although probably intended to be admired from a distance, this cherub is intricately detailed and exquisitely rendered: the face and hair are elegantly outlined and the feathers are textured through juxtaposed lines. The marble, both figurative and decorative, adheres to the principles of balance and restrained ornamentation typical of the « Florentine Classicism ». Harmonious shapes and gracefully orchestrated curves , rooted in the classical repertoire, converge to evoke a sense of ethereal beauty. The surface displays the masterful use of a chisel to intricately carve the feathers and facial features, creating an almost abstract quality.

This work is a testament to a sculptor of great skill and rich figurative knowledge, seamlessly blending classical firmness in contours with a refined treatment of the marble’s surface. The combination of tradition and innovation point to a stylistic idiom from Lombardy, in particular we can find some comparaisons with the works of Jacopo della Pila, sculptor of Lombard origin working in Naples in the second half of the 15th century. He is documented there between 1471 and 1502, and is a protagonist of the Aragon Renaissance in the second half of the Quattrocento, together with the other great Northern sculptor active in the kingdom, Domenico Gagini.

the first commission he received dates back to August 9, 1471, when Jacopo publicly committed to sculpting the funerary monument of Archbishop Nicola Piscicelli to be placed in the Cathedral of Salerno. The last known work is an altar ordered on July 29, 1502, by the noble Jacopo Rocco for the church of San Lorenzo Maggiore in Naples. Between these two chronological extremes (1471-1502), we must place the fervent activity of the artist, who had trained in Rome, perhaps under the guidance of Paolo Romano but also engaged in dialogue with other major artists of the city, especially Isaia da Pisa. He enriched his experience in Naples, initially drawing inspiration from the works of Domenico Gagini and later from the Tuscan masterpieces of Antonio Rossellino and Benedetto da Maiano destined for the church of Santa Maria di Monteoliveto. Jacopo della Pila’s artistic personality is thus based on a complex interplay of influences, contributing to the definition of a highly personal style.

Close comparaison can be made between our cherub and the winged angels reliefs in the Brancaccio tomb by Jacopo dalla Pila. Both reliefs stands out for their purity of form, rigor and minimalism inspired by the Florentine repertoire but also marked by the influence of early renaissance sculpture in Lombardy visible in the clear lines and simplified volumes.

Another work by Jacopo della Pila can be connected to the current relief. The cherub’s head, sculpted by the artist for the Church of Santa Maria di Monteoliveto, shares similar stylistic features, especially in the treatment of the arches above the eyebrows and well-defined eyelids, which give the cherub a haughty expression. The slightly flattened nose, expanding in width, along with the disheveled locks of hair, imparts a distinctive physiognomy to the cherubs. In both reliefs, although the wings are in different positions, they reach the edges, occupying the entire space of the panel and are marked by similar “herringbone” incisions.

This beautiful relief of a cherub stands as a harmonious synthesis of late-Gothic reminiscences, Tuscan influences, and Nordic elements, exemplifying the rich cultural tapestry of Naples during the Renaissance era. The work perfectly embodies the concept of Maria Accascina : Renaissance sculpture in south of Italy was not the result of a « maturation process » or « production » but rather an « import owed to maestros from Lombardy and Carrara ».

Related Literature:

M. Accascina, Inediti di scultura del Rinascimento in Sicilia, in Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz, XIV (1970)

Yoni Ascher, Tommaso Malvito and Neapolitan Design of Early Cinquecento, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institute, Vol. 63, 2000, pp. 111-130

Maria Grazia d’Amelio, Opus incertum, soffitti lignei a lacunari a Firenze e a Roma in età moderna, Rivista di storia dell’architettura università degli Studi di Firenze, 2017

Dentamaro, Antonella. “Qualche Novità Su Jacopo Della Pila, Con Una Digressione Su Alcune Sculture Napoletane Nel Victoria and Albert Museum.” Prospettiva, nn. 167-168 (2017)

Antonella Dentamaro, TABERNACOLI E ALTARI EUCARISTICI DEL RINASCIMENTO IN CAMPANIA, tesi di dottorato, 2013-2014, Università degli studi di Napoli, dipartimento di studi umanistici

R. Pane, Il rinascimento nell’Italia meridionale, vol. ii (Milan, 1977)

B. Patera, ‘Scultura di rinascimento in Sicilia’, Storia dell’ arte, 24/25 (1975)

Michalsky Tanja, “‘Tombs and the Ornamentation of Chapels.’” Artistic Centers of the Italian Renaissance – Naples (2017): 233–298.

Olimpia Ratto Vaquer, Note intorno alla cappella del succorpo a Napoli, Giuliano da San Gallo e i Propilei di Atene, 2021