Provenance : Private collection Brugge, Belgique

This intriguant and rare engaged capital is decorated in two sides with stylized lions around a human bust; the base consiste of a simple roll moulding. The capital is carved only in two sides suggesting that it would have originally been in a corner, where it may have supported a wooden roof or an arch. The fine carving of this piece survives in a very good condition.

The low relief figures of two confronting and opposing lions are stylized but interpreted with an elegant and ornamental design, with incised details of the tail and the mane. The three wild animals are represented in rampant position with long manes and tails ending in a tassel. The symmetrical back-to-back arrangement of the beasts resembles the decorative motifs of textiles imported from the islamic or Byzantine world. During the Middle Ages, the artistic connection was possible through Mediterranean trade routes. Emile Mâle argued that many of the animal motifs, and prominent among them most lions, were borrowed from Eastern textile art, which was well known in Medieval Europe.

The faces of all three creatures are carved with cat-shaped ears, circular incised eyes with drilled pupils and enrolled incised tails. The relief follow a symmetrical compositional formula, that was favored in Romanesque sculpture.

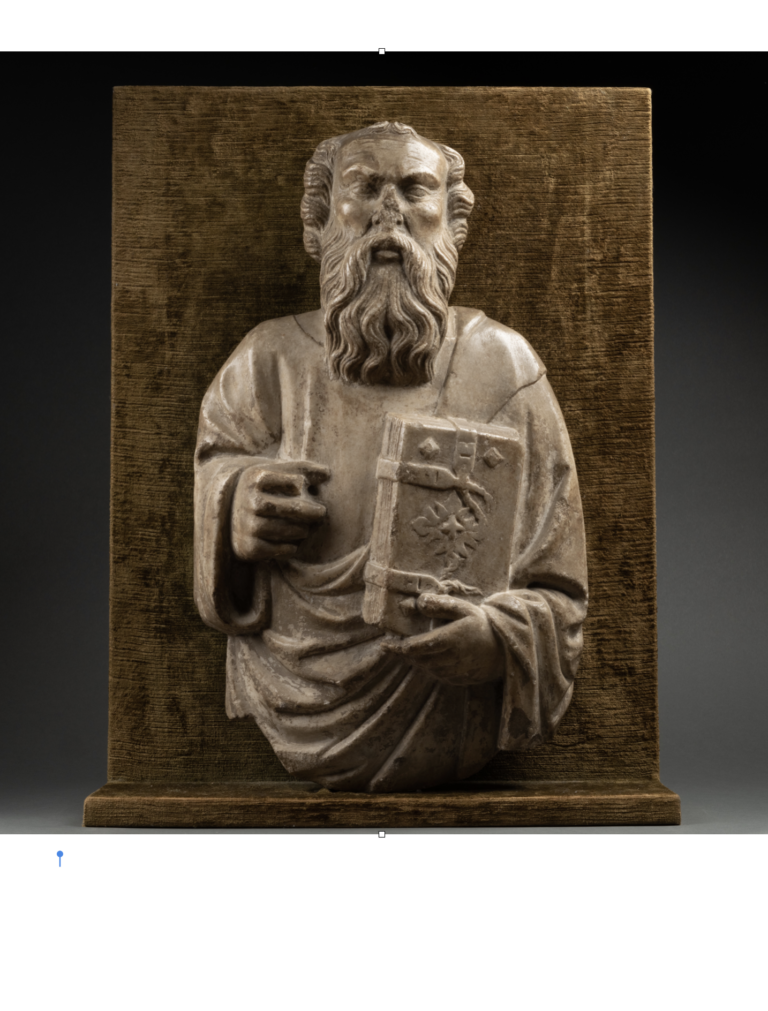

The iconography, Showing a human figure flanked by lions, is a common theme in Romanesque churches and was one of the most Ancient images known to man, emerging out of Sumeria in the third millennium BC.

It probably represents the history of Daniel in the Lion’s Den which was one of the most iconic scene in the whole Romanesque canon. A capital showing the same motif is preserved at Saint Pierre de Mossac.

In both capital, the half-figure of Daniel occupied the central position and the lions surrounds him in symmetrical position.

The story is taken from Chapter six of the Book of Daniel. The Old Testament recounts how the Persian king Darius I “The Great” (550–486 BC) condemned the devout and steadfast Daniel to spend the night in a lions den for worshipping God rather than him. The following morning, after the stone sealing the entrance was rolled away, the astonished Persians saw Daniel, very much alive, giving thanks to God for keeping him safe overnight: “Then said Daniel unto the king :« O king, live for ever. My God hath sent his angel, and hath shut the lions mouths, that they have not hurt me: forasmuch as before him innocency was found in me; and also before thee, O king, have I done no hurt.” (Daniel 6:21–22)

For theologians, Daniel’s miraculous survival in the cave symbolized the resurrection of Christ from his tomb, and the promise of God’s protection to those of unwavering faith.

The Daniel legend found its way into early funerary prayers. Depictions were a feature of the first Christian art of the Roman catacombs and were widely used on sarcophagi of Late Antiquity. Hippolytus of Rome was the author of the first commentary on Daniel just after the turn of the third century. Drawing on the notion of Daniel, who by his faith in God evaded death at the hands of the lions, Hippolytus found parallels with the Resurrection. Daniel, he equated with Adam as a precursor of Christ and the lions represented Death overcome.

The Book of Daniel continued to be the subject of numerous commentaries from authors including Jerome and Ambrose of Milan and throughout the middle ages in texts by the Benedictine monks Raban Maur and Honorius of Autun.

The Den was an image of Hell, wrote Didymus the Blind in his fourth century Commentary on Zechariah: “Ask yourself if the Den without water is not the Hell of the impious and sinners”. With the lions symbolizing Death, a common reading was to equate Daniel’s survival with Christ’s triumph over Death. Thus the image read as a descent into Hell and a resurrection and therefore a prefiguration of Christ’s Passion and Resurrection.

Ultimately the image of Daniel in the Lion’s Den was seen as a symbolic representation of Paradise. Daniel was guarded by the lions. Aprahat wrote that the lions extended their paws to cushion Daniel’s fall into the Den. Ambrose and Paulinus of Nola echoed this notion.

The person of Daniel was also taken to represent the Christian believer whose own death and resurrection were implicit in the Daniel legend.

This broad range of allegorical readings of the narrative can be found represented in the rich variety of the depictions in Romanesque sculpture.

Related Literature :

- R. B. Green, Daniel in the Lion’s Den as an exemple of Romanesque typology, The University of Chicago, Dissertation, 1948

- Emile Mâle, Religious art in France. The Twelfth century, Princeton 1978

- Tina Negus. Daniel in the Den of Lions: early medieval carvings and their origins. Journal of Ethnological Studies. Vol.44