Provenance:

Collection Raymond Van Marle (The Hague 1887 – Perugia 1936)

Solomeo (Perugia, Italy)

Bibliography:

– Federico Zeri Foundation – University of Bologna;

– Federico Zeri Photo archive n° 10429;

– Alinari – Brogi Archive: BGA-F-025726-0000;

– Photographer, Brogi 1936, Corciano, Solomeo, private collection Raymond Van Marle

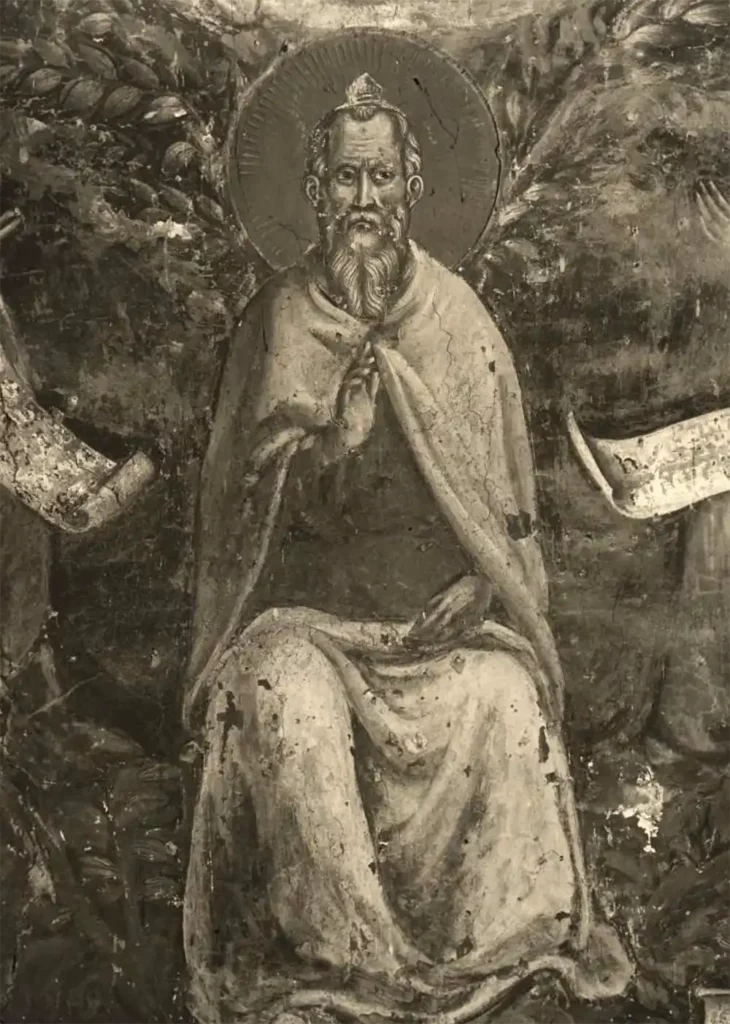

St. Bartholomew was one of the twelve apostles of Jésus according to the New Testament. The Saint is depicted holding a book and a knife symbolizing his death by flaying. The appearance of the St Bartholomew is described in detail in the golden Legend : « His hair is black and crisped, his skin fair, his eyes wide, his nose even and straight, his beard thick and with few grey hairs; he is of medium stature ».

His wrinkles, hair and drapery are observed with a delicate realism which offers the first whispering of the Renaissance. Byzantine linear treatment of draperies is severely reduced in favor of rounded modeling, and the traditional linear definition of facial features is completely abandoned.

There is a strikingly new spatial clarity and sculptural approach to the figures and a use of light that is unprecedented in Italian art; the light strikes the figure from one direction and serves to mold and reveal, rather than decorate, the form. The artist sought to overcome the flatness of the forms and compositional structure inherent in the Italian painting of the XIII century, giving the images a volumetric plasticity.

Cavallini blended influences of classical Roman forms combined with the Byzantine artistic heritage of the region and with northern Gothic influences to spark an interest in volumetric, naturalistic paintings.

The fresco was first attributed to Pietro Cavallini By Van Marle who published a monograph about the painter in 1921; Federico Zeri, the most prominent Italian art historian, corroborate this hypothesis and in the ’70 published the fresco in his photothèque archives (university of Bologna) and ascribed it to an Umbrian artist working alongside Pietro Cavallini.

This attribution to an Umbrian artist came during the discussion about the Assisi’s frescos which Zanardi attributed to Pietro Cavallini and his cercle. Zeri was convinced that Pietro Cavallini worked in the fresco’s alongside Umbrian artists, influencing and renovating the local artistic production. Vasari attributed the Assisi’s frescos to Giotto who in his opinion single-handedly started the Renaissance. Vasari is followed by two highly influential art historians whose writings inspired countless trips and tour guide talks in Italy. “For Giotto to break away from Byzantine painting and evolve this solid, space-conscious style was one of those feats of inspired originality that have occurred only two or three times in the history of art,” wrote Kenneth Clark in Civilisation. Ernst Gombrich noted the same in The Story of Art, still a standard textbook for first year art history students: Giotto was “the genius who broke the spell” of the “frozen solemnity of Byzantine painting… Nothing like it had been done for a thousand years.” Bruno Zanardi, an Italian picture restorer, published Il cantiere di Giotto: a detailed account of Giotto’s Assisi cycle. Zanardi says Giotto did not paint it. Three different “masters” worked on the cycle – none of them Florentine; they were all from Rome, and one Pietro Cavallini was responsible for the largest segment.

Federico Zeri has come out in vociferous support of Zanardi’s claims. He believes that Zanardi has “settled the question.”

Zanardi reaches his conclusions by exhaustive analysis of the techniques and materials used to construct the Assisi cycle. Whereas traditional art history determines questions of attribution on the basis of aesthetic style, Zanardi examines how the painting was made: the chemical composition of the paints, the method used by the head of a workshop to impose his style on his assistants, and the precise way in which he made brush strokes.

Until the turn of the twentieth century, no paintings by Cavallini were known to have survived. The prevailing view of his art was derived from Vasari, who places him too late in his Lives and claims that he was a disciple of Giotto, who was actually younger.

Panowsky wrote : « Pietro Cavallini pourrait prétendre, aussi valablement que Cimabue, être le maître de Giotto en tant que peintre florentin transformé par son expérience romaine » .

in the early 1290s Cavallini executed his most famous works : the frescoes of Old Testament scenes (only fragments survive), and an Annunciation in Santa Cecilia in Trastevere in Rome. Here the classicizing elements of his mosaics are consolidated in a powerful and grandly expressive style best illustrated by a beautiful and lively group of seated Apostles, highly individualized, whose solidity of form is completely successful in defining the space around them. A further important feature is the use of soft, rich color harmonies and shading. In 1308 Cavallini was invited to Naples by Charles of Anjou; there he came into contact with the graceful forms of Gothic art of the northern Anjou country. Most of his works of the Roman period, mentioned by Ghiberti and Vasari, is not preserved (e.g., mosaic, executed about 1321 for the facade of the Basilica of San Paolo in Rome) but it is well-known by the works of his many pupils who carried on his tradition.

The discovery of the Santa Cecilia frescoes led to a reappraisal. Cavallini’s art is now seen as a climax of an artistic revival in Rome that started slightly before Giotto and included the reinvention of the technique of true fresco. He softened the rigidity of Byzantine art, and his majestic figures have a real sense of weight and three-dimensionality. His achievements were built on by his great contemporary Giotto, whose Last Judgement in the Arena Chapel at Padua features Apostles enthroned exactly as in Cavallini’s fresco of the subject. Cavallini is thought to have begun the movement away from the popular Byzantine style by blending it with a vivid naturalism, northern European styles and the artistic traditions of early Christian Rome.

His importance is founded on three interrelated factors. First, his style displays a new vision of the human figure and, as he was active in Rome before Giotto, it is probable that the new style Giotto brought to Tuscan art was indebted to Cavallini. Second, he reached artistic maturity at a time when the papacy, from the reign of Nicholas III (1277–80) onwards, was re-establishing its presence in Rome by the institution of large-scale artistic projects, so providing artists with opportunities to produce influential work on a monumental and prominent scale; and third, he is one of the first medieval artist whose identity and personality are known.

Along with Giotto, Cimabue and Duccio, Cavallini occupies an important place in the history of Italian painting of the late ducento and the beginning of the trecento. Raised in the Byzantine tradition, he did not obey her common mannerisms, but, on the contrary, tried to recreate the most high and the ancient forms went the way of the great Roman medieval painting. Margaret Field wrote in her dissertation : « no doubt Cavallini was for the roman school what Giotto was for the Florentine and Duccio for the Sienese school ».

The prestigious provenance of this painting which was a part of the renewed art historian and connaisseur collection (in Solomeo, Perugia, Umbria) of Raymond Van Marle (The Hague 1887 – Perugia 1936) was documented since 1936 in the alinari-brogi archive.

Art historian, iconographer, and connoisseur, Van Marle studied in Paris at the école des Chartes and the école Pratique des Hautes études. His earliest writings are on Dutch medieval history. After his marriage, he settled in Perugia in 1918, where he could afford to live without employment, dedicating his life to art-historical research.

He wrote several studies on Italian painting and iconography. In 1923 he began publishing his monographic series on Italian paintings which covered the early Christian era to the end of the Quattrocento, The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting (21 volumes, 19 published).

Another important work by Van Marle is his two-volume Iconographie de l’art profane au Moyen-âge et à la Renaissance, et la décoration des demeures, published in 1931-32. It deals with a large variety of representations of daily life, and allegories and symbols, decorating churches, illuminated books and dwellings.

One of his statements was the suggestion that a modern art historian has to take into account both the results of archival research and those of connoisseurship. His knowledge was almost encyclopedic and his connoisseurship lead him frequently to new discoveries and attributions, which he published in various international magazines and journals. Van Marle employed psychological analysis to his subjects. John Presland described him as a cosmopolitan and a humanist, likening him to Erasmus of Rotterdam.

Bibliography:

- Brentano Robert, Rome Before Avignon: A Social History of Thirteenth-century Rome, (University of California Press, 1991), 67.

- Kenneth Clark, Civilisation, John Murray, 1969

- Cooper Donald, Giotto e Pietro Cavallini. La questione di Assisi e il cantiere medievale della pittura a fresco by Bruno Zanardi, The Burlington Magazine, 146, 2004

- Irene Margaret Field, Pietro Cavallini and his school : a study in style and iconography of the frescoes in Rome and in Naples, Thesis (Ph. D.)–University of Wisconsin, 1958

- Ernest Gombrich, the history of art, phaidon press, 2006

- Paul Hetherington, Pietro Cavallini, Artistic style and patronage in Late Medieval Rome, The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 114, No. 826 (Jan., 1972), pp. 4-10

- Panofsky E. La Renaissance et ses avant-courriers dans l’art d’Occident. Flammarion 2008

- Alessandro Parronchi, Cavallini « discepolo di Giotto, Edizioni Polistampa, Firenze

- Presland, John in The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting, 16, The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1937

- R. Van Marle, La scuola di Pietro Cavallini à Rimini, in Boll. Arte, I, 1921, pp.248-261

- Bruno Zanardi, Giotto e Pietro Cavallini. La question di Assisi e il cantiere medievale della pittura a fresco., Skyra, 2002

- Federico Zeri archive, University of bologna, n° 10429