These two rare bronze statuettes represent two figures dressed in elaborate “Turkish” attire. They are mounted on alabaster bases with bronze reliefs—one featuring the winged lion of Venice, and the other possibly symbolizing Turkey with a wolf depiction.

One figure wears a grand külah, a spherical turban with a cone top, signifying royal authority, while the other has a wrapped turban, denoting rank and religious identity. Their garments are richly detailed with intricate engravings, suggesting luxurious fabrics of the Ottoman court.

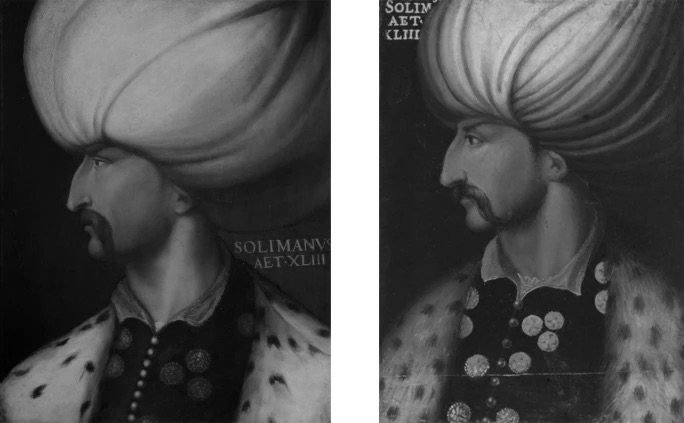

SULEIMAN THE MAGNIFICENT (1520–1566), PORTRAIT COLLECTION OF ARCHDUKE FERDINAND II OF TYROL (1529-1595), PICTURE GALLERY, KUNSTHISTORISCHES MUSEUM VIENNA

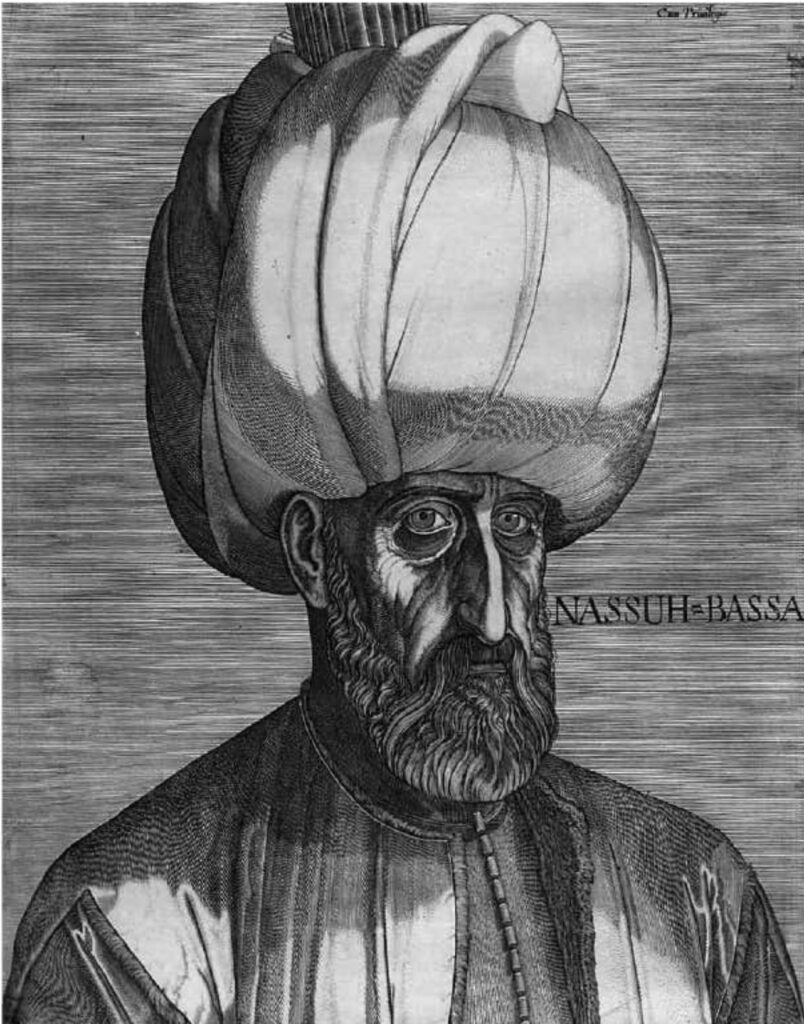

The statuettes may represent Suleiman the Magnificent at two different stages of life, as both young and old. The sultan depicted alongside the winged lion corresponds to a description from a Venetian delegate in 1534, when Suleiman was 43. At that time, he had conquered Iraq from the Safavids and achieved a decisive victory over the Papal fleet at the Battle of Preveza. He was described as having large eyes, an aquiline nose, and long red mustaches—traits visible in Cristofano dell’Altissimo’s portrait of Suleiman in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence.

Unlike Mehmed II, who commissioned portraits by European artists for diplomatic purposes, Suleiman did not directly order such representations. Instead, his likeness spread through works by artists like Albrecht Dürer, based on sketches made by diplomats. Following his capture of Belgrade in 1521, his victory over Hungary in 1526, and his siege of Vienna in 1529, Suleiman gained international fame. He was both admired and feared by rulers across Europe and recognized as one of the most illustrious figures of his era.

The winged lion and Turkish wolf accompanying the bronzes suggest a political and diplomatic significance, reflecting the complex relationship between Venice and the Ottoman Empire. Despite ongoing territorial disputes and wars, both powers sought peaceful coexistence, driven by the need to sustain trade. Venice and the Ottomans signed multiple treaties during the reigns of Mehmed II and Suleiman. After the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, where the Holy League (including Venice) defeated the Ottoman fleet, relations were strained but soon restored. Venice, prioritizing its economic interests, signed a peace treaty with the Ottomans in 1573, allowing the Serenissima to maintain vital trade routes and Mediterranean stability.

The presence of the winged lion alongside a sultan emphasizes Venice’s intent to foster positive relations with the Ottoman Empire. These bronzes may have been created after one of the many peace treaties between the two powers. Bronzes, sculptures, clocks, and medals were typical diplomatic gifts from Venetian representatives, and these statuettes, symbolizing the close ties between the Serenissima and the Ottoman Empire, were likely presented to an Ottoman ambassador during one of the peace agreements of the 16th century.

European perceptions of the Ottomans were complex. While the empire posed a significant threat, as during the siege of Vienna, trade and diplomacy continued to prevail, fostering a lasting cultural exchange between East and West well into the 17th century.

Bibliography:

Bellingeri, Giampiero. “Turchi e Persiani fra visioni abnormi e normalizzazioni, a Venezia (secoli XV-XVIII).” In RILUNE — Revue des Littératures Européennes, no. 9, “Visions de l’Orient,” edited by Benedetta De Bonis and Fernando Funari, 2015, pp. 14-89

Bevilacqua, Alexander. The Republic of Arabic Letters: Islam and the European Enlightenment. Harvard University Press, 2020.

Born, Robert, Michal Dziewulski, and Guido Messling. L’Empire du Sultan: Le Monde Ottoman dans l’Art de la Renaissance. Lannoo – Bozar Books.

Etrangers et Vénitiens dans l’art du XVIIe siècle. Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 2018.

Pessa, L. “Figure di Turchi nell’arte genovese tra XVI e XVII secolo.” In Turcherie, cited in note 98, pp. 40-42.

Renard, Alexis. Turkophilia Révélée: L’Art Ottoman dans les Collections Privées. 14th International Congress of Turkish Art, 2011.

Weihrauch, H.R. Europäische Bronzestatuetten. Brunswick, 1967.