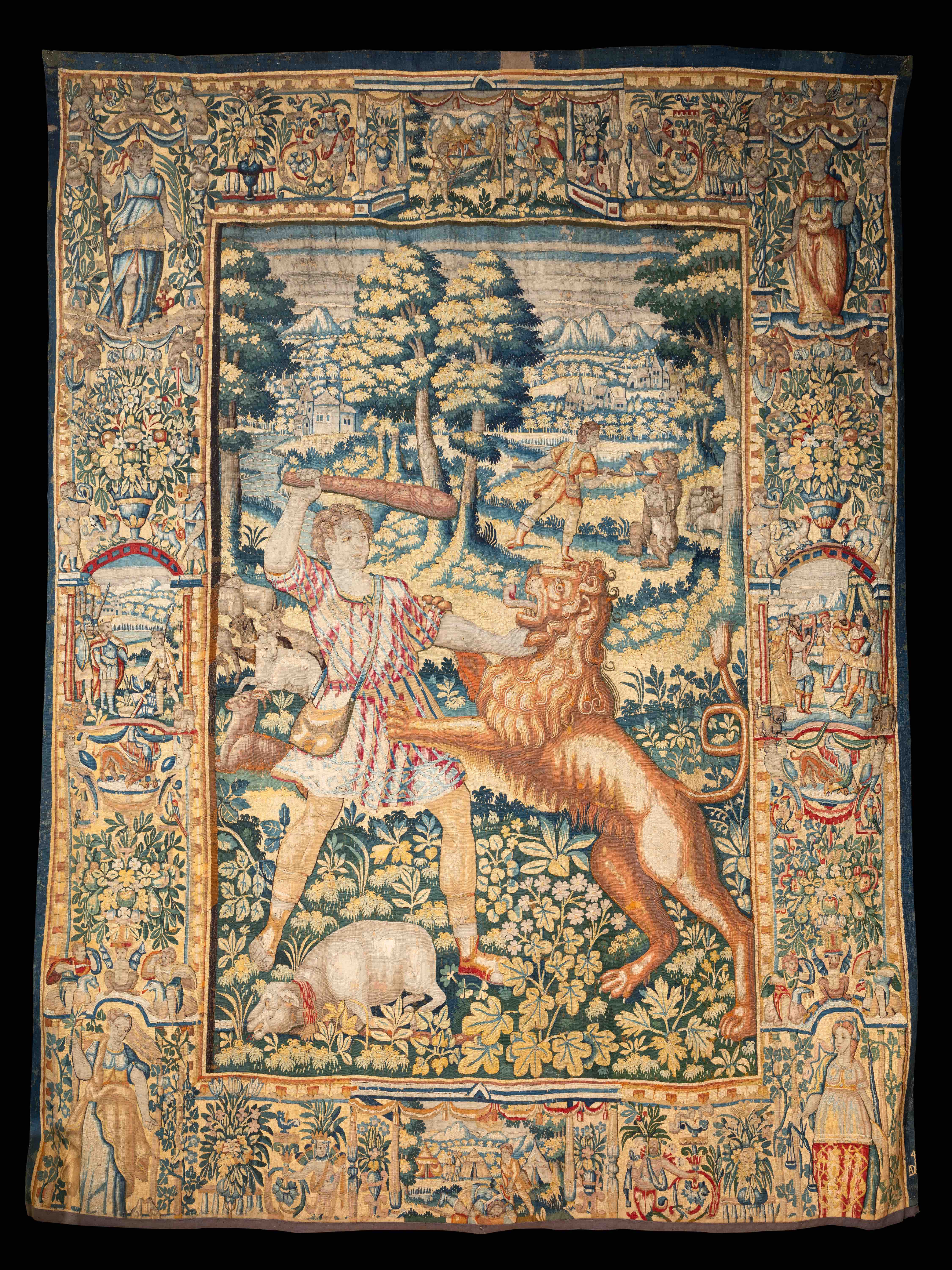

This splendid Brussels tapestry, crafted from wool and silk during the 16th century, bears the monogram of the weaver’s workshop at its lower left corner.

The tapestry narrates the story of David, with a particular focus on the episode of the young shepherd’s battle against formidable adversaries: the lion and the bear. The Bible recounts David’s struggle against Goliath, a tale pivotal in ending the war between the Philistines and the people of Israel. Within this narrative, the accounts of David’s previous clashes with the lion and the bear are intricately woven.

The confrontation with Goliath stands as one of the most renowned episodes in the wars between Israel and the Philistines. Goliath, a giant standing at 9 feet 2 inches, hailing from the city of Gath, challenged the entire army of Israel to single combat for 40 days, with no one daring to face him. It was David, who, sidelined from the war due to his youth, volunteered to confront Goliath when he arrived to supply his brothers with provisions.

The central scene depicted in the tapestry portrays David’s battle against the beasts, which aimed to persuade King Saul to allow him to face the giant despite his youth. The crux of this episode lies in the unwavering faith that fuels David and the divine protection that accounts for his remarkable victory. David, drawing a parallel, states, ‘When your servant was tending his father’s sheep and a lion or a bear would come and carry off a sheep from the flock, I would go after it, strike it, and rescue the sheep from its mouth. If it turned on me, I would seize it by the jaw, strike it, and kill it. Your servant has killed both the lion and the bear; this uncircumcised Philistine will be just like one of them, since he has defied the troops of the living God. David added, ‘The Lord, who saved me from the paw of the lion and the paw of the bear, will save me from the hand of this Philistine.’ So Saul said to David, ‘Go, and may the Lord be with you.’

David, a shepherd under his father Jesse, was soon recognized as a representation of the Son of God, who became the Son of Man to manifest to humanity. David, the shepherd who risked his life to face the beasts and ensure the sheep’s salvation, was an unmistakable figure of the Good Shepherd who ‘lays down his life for his sheep.’ The episode of David’s triumph over the lion and the bear can be counted among the symbols of Christ’s Paschal victory over Satan, rescuing humanity.

According to Hippolyte, the lion symbolize death and the bear represents sin. From the Christological interpretation where David conquers the lion and the bear symbolize Christ’s triumph over infernal powers, one naturally transitions to a moral exegesis: just like David, Christians are called to conquer evil and sin. Wealthy patrons often commissioned designs whose subjects embodied celebratory or propagandistic themes. The patron of tis tapestry was not indifferent to the wealth of Christological motifs in the figure of David. As king, prophet and shepherd, David has his place in the history of Salvation between Adam and Christ, as a representation of humanity seeking reconciliation with God.

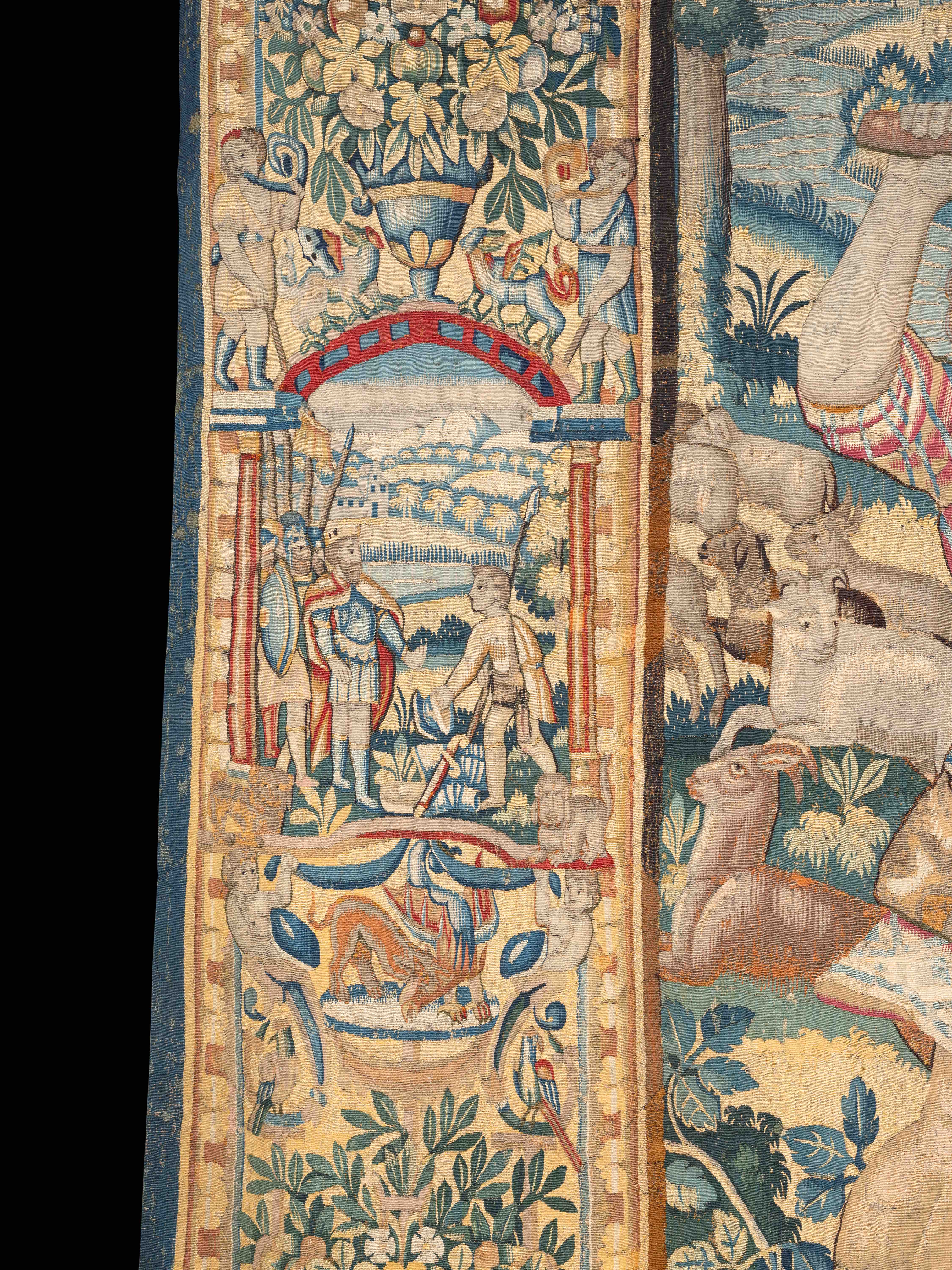

The tapestry is framed within a beautiful and expansive border richly adorned with compartments. It is representative of many Brussels series from the third quarter of the 16th century, featuring the grotesque style popularized by Raphael’s school in the first half of the 16th century, incorporating sphinxes, vases, flower garlands, and small colonnaded structures.

This exquisite decoration draws inspiration from the paintings found in the Domus Aurea (Golden House) discovered in Rome in 1493. Filled with animal allegories borrowed from late Antiquity treatises, such as those of Pliny, these images serve as allusions to the moral virtues illustrated in the central scene. The virtues showcased at the four corners of the tapestry are typical of the late 16th century and frequently appear in Brussels, Tournai, and Enghien workshops.

Four episodes from the story of David, integrated into the border, complete the iconographic program of the central scene. In the upper part of the tapestry, we find the scene where David decides to face Goliath armed only with a shepherd’s staff and a flat stone, while the lower part portrays the death of the giant at the hands of young David. On the left, another scene depicts David at Saul’s court, playing soothing music on his harp to alleviate the king’s bouts of depression. On the opposite side, we see David journeying to the camp of the Israelites to deliver food to his brothers engaged in battle against the Philistines, and at this moment, he hears Goliath’s challenge to send a champion to fight him. Saul offers David armor to confront the giant, but the young shepherd chooses to fight without armor, relying on the protection of God.

At the bottom left of the border, the monograms « ADE » appears as a signature. Monograms, often discreetly integrated into the intricate patterns, served as a mark of individual craftsmanship or identified specific workshops. These artistic signatures conveyed a sense of pride and authorship. Weavers, who often remained anonymous in the historical record, left their mark through carefully placed monograms, creating a visual legacy for their contributions to these magnificent textiles. In the intricate world of Brussels Renaissance tapestries, monograms emerge as silent yet powerful testaments to the craftsmanship, collaboration, and individuality that defined this remarkable period in art history.

A close comparison can be drawn with a 16th-century tapestry crafted by Martin Reymbouts. Noteworthy is the resemblance of the monogram in the lower left section and the border, richly adorned with grotesques. The facial features of the characters, along with their “a l’antica” attire and the treatment of the landscape, exhibit similarities that help in dating our tapestry to the latter half of the 16th century. It is worth noting that the lower edge of our tapestry has been slightly shortened, impacting the visibility of the monogram of the city of Brussels, which was originally positioned on the lower right edge of the artwork (B B).

In addition to symbols of wealth and prestige, tapestries served functional purposes such as providing insulation for castle walls, covering openings and providing privacy in bedrooms.

While repetitive and decorative patterns like verdure or armorials persisted, historiated tapestries gained increasing interest. The subjects often allowed for the portrayal of a character trait, virtue, or an episode from the patron’s life.

By the early 16th century, the Netherlands was one of the unrivaled centres of tapestry production in Europe, with the majority of industry concentrated in Brussels. During the second quarter of the sixteenth century, the volume of lucrative commissions from the foremost courts of Europe encouraged even greater specialization by Brussels cartoonists and weavers, leading to extraordinary technical and artistic achievements.

They were particularly admired for their ability to capture texture, light, shadow, and relief effects using threads of various colors, similar to the nuances in paintings.

Some Brussels craftsmen even relocated to various parts of Europe, often close to the monarchs’ residences. Furthermore, renowned painters sent their designs to Brussels to be executed into tapestries.

Tapestry manufacturing was a highly organized and standardized business involving fine artists, weaver’s guilds, large financiers, dealers and royal commissions. LARGE, NARRATIVE TAPESTRIES, were the result of a collaborative process that included, in essence, three stages: First, the designer sketched the preliminary composition for the tapestry and reined this into a more detailed rendering, called in Dutch the patroon int klein, petit patron in French. Second, a painter copied the design of the petit patron, enlarged to the tapestry’s intended size, onto a tapestry-sized piece of cloth or, increasingly more commonly, a large expanse of paper sheets pasted together. This painting, referred to as the cartoon, was the final template, or model, for the tapestry’s design. In the third step of the process, the cartoon was handed over to the master tapestry weaver, whose team of journeymen weavers would weave the tapestry using the cartoon as their guide. Occasionally, weavers implemented small changes to the design, such as variations in thread colors. Thus, the finished tapestry was a collaboration that typically reflected the artistic input of many hands beyond those of the initial designer. Tapestries are made by weaving together two sets of threads known as the warp and the wefts. Warp threads are the support, like a blank canvas, and on to them are woven perpendicularly the weft threads, which provide the colors that gradually build up to form a tapestry’s picture, like strokes of paint on that canvas. A tapestry’s warp threads are usually undyed and are made of wool or linen. These threads are stretched vertically over the loom. Weft threads usually comprise colored wool, silk, and, sometimes, precious-metal-wrapped threads. Weavers intertwine these threads in an orderly, grid like fashion by inserting a variety of weft threads over and under the warp threads with shuttles on to which the colored threads are spooled, then tamping the wefts so tightly together that they conceal the warp from view. Warps are the backbone of every tapestry and provide the foundation for the wefts; although hidden from view in a finished tapestry, the warp threads are vital components and the very elements that give tapestries their distinct, ribbed texture and their strength. Wefts, because they are introduced only where the design demands a patch of that particular color, are rarely woven in and out across all the warps. Rather, they are incorporated in areas as dictated by the cartoon’s design. When weavers need to introduce a new color, they knot the existing weft in place, snip off or tuck in any loose ends, and add another color using a different weft thread; these are called “discontinuous wefts”. Examination of the reverse side of a tapestry reveals the various methods weavers used to change colors: gradual hatching, distinct slits, or structurally more complex interlocked wefts. Tapestry backs, because they are seldom seen and rarely encounter direct exposure to light, do not fade as severely as the fronts of tapestries and therefore preserve a truer sense of wefts’ original depth of color. Historically, weavers worked facing what would be the back of the tapestry, using either a high-warp (vertical or low-warp (horizontal) loom. For work on low warp looms, the tapestry cartoon would be cut into strips and placed directly beneath the loom’s warp threads. With high-warp looms, the cartoon was hung either flush against the back of the warp threads or on the wall behind the weavers. If the cartoon was hanging behind the weavers, they would replicate the design by looking at its reflection in a mirror positioned behind the warps. Because the weavers copied the cartoon working on the back of the tapestry, when the tapestry was finished, removed from the loom, and turned over to reveal its front, the woven representation was the reverse of the cartoon. However, when they used the high-warp loom mirror method to copy the cartoon’s design, weavers avoided this reversal. On both kinds of looms, the tapestry cartoon was turned at a ninety-degree angle to the warp threads , meaning that weavers were copying the cartoon’s design sideways. This way, when the finished tapestry was hung, the warp threads that were vertical on the loom would become more supportive horizontal elements. This would also allow for monumentally wide tapestries to be woven without the need for massive, equally wide looms. The cartoon was not physically part of the completed tapestry and could be reused multiple times in order to make duplicate tapestries.

The cost of labor and raw materials, including wool, silk, and gold threads, necessitated significant financial investments. These workshops were essentially enterprises managed by weaving dynasties. Consequently, Brussels’ tapestries elevated the city’s status as a stronghold in the European luxury market. These Brussels tapestries, whether used for devotion or as a medium for displaying power, found their way to numerous European courts.

From the Dukes of Brabant to the Dukes of Burgundy, and even the court of Emperor Charles V, Brussels fabric was highly sought-after during the transition from the Middle Ages to the Early Modern Period. It traveled as far as the court of the King of France and the Pope in Rome, from Cracow’s castle to the London residences of Henry VIII. At the time, it was the most expensive prestige product in Europe.

The “movable frescoes of the North,” as they were termed, held a prominent place in the grandeur of princely residences during this era.

Bibliographie:

- Campbell, Thomas, Tapestry in the Renaissance, Art and Magnificence, Metropolitan Museum of Art Exhibition, March-June 2002, Yale University Press 2002

- Cavallo, Adolph, Medieval Tapestries in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1993, Stylistic Development of Tapestry Design in France and the Southern Netherlands, 1375-1525

- E. Cleland, Grand Design, Pieter Coecke van Aelst and Renaissance Tapestry, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Yale University Press, New Haven and London

- E. Dhanens, « the David and Bathsheba Drawing »,Gazette des Beaux-Arts, ser.6, 53, 1959

- Delmarcel, Guy. Flemish Tapestry: From the 15th to the 18th Century. Translated by Alastair Weir. Tielt, Belgium: Lannoo, 1999.

- M. Dulaey, La lutte de David contre les monstres: le lion, l’ours, Goliath (I R 17) dans Rois et Reines de la Bible au miroir des pères, Cahiers de Biblia Patristica, Strasbourg 1999, p. 7-51

- Joubert, Fabienne, et al. Histoire de la tapisserie en Europe, du Moyen Âge á nos jours. Paris: Flammarion, 1995.