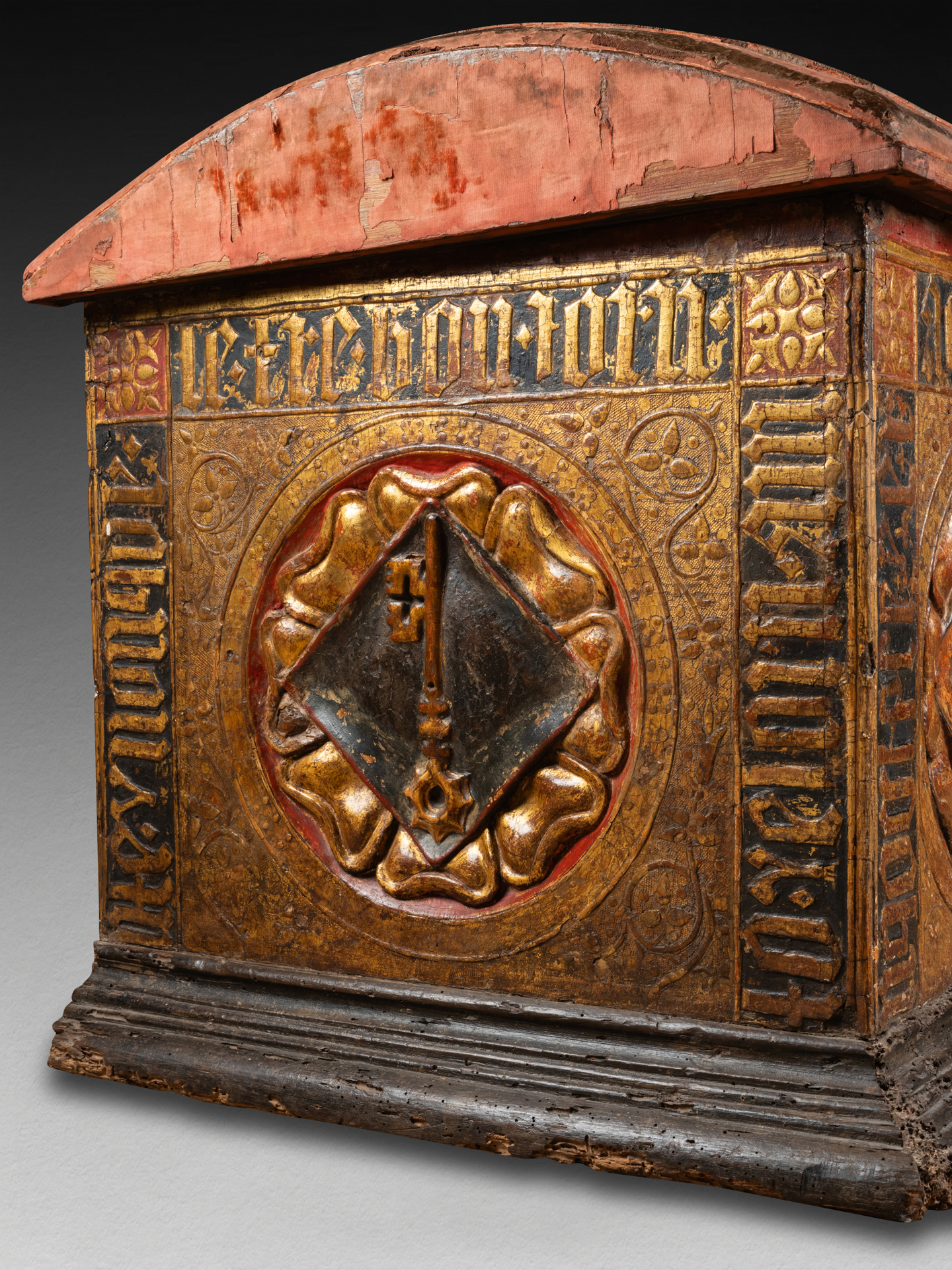

Richly decorated wooden chest with gilded punchwork and polychrome in red and black, featuring a hinged, purple velvet-covered lid. The chest is rectangular in shape with a stepped base, and the lid is domed. The structure of this chest is simple, with no complicated building details, as was the norm in the Western Mediterranean area in that period. It is made of large wood panels and the convex shape of the lid has been obtained by juxtaposing a number of boards sawn in a slight curve. In this way it is possible to obtain ample homogeneous surfaces, adequate for decorating in one piece without the limitations imposed by a complicated construction.

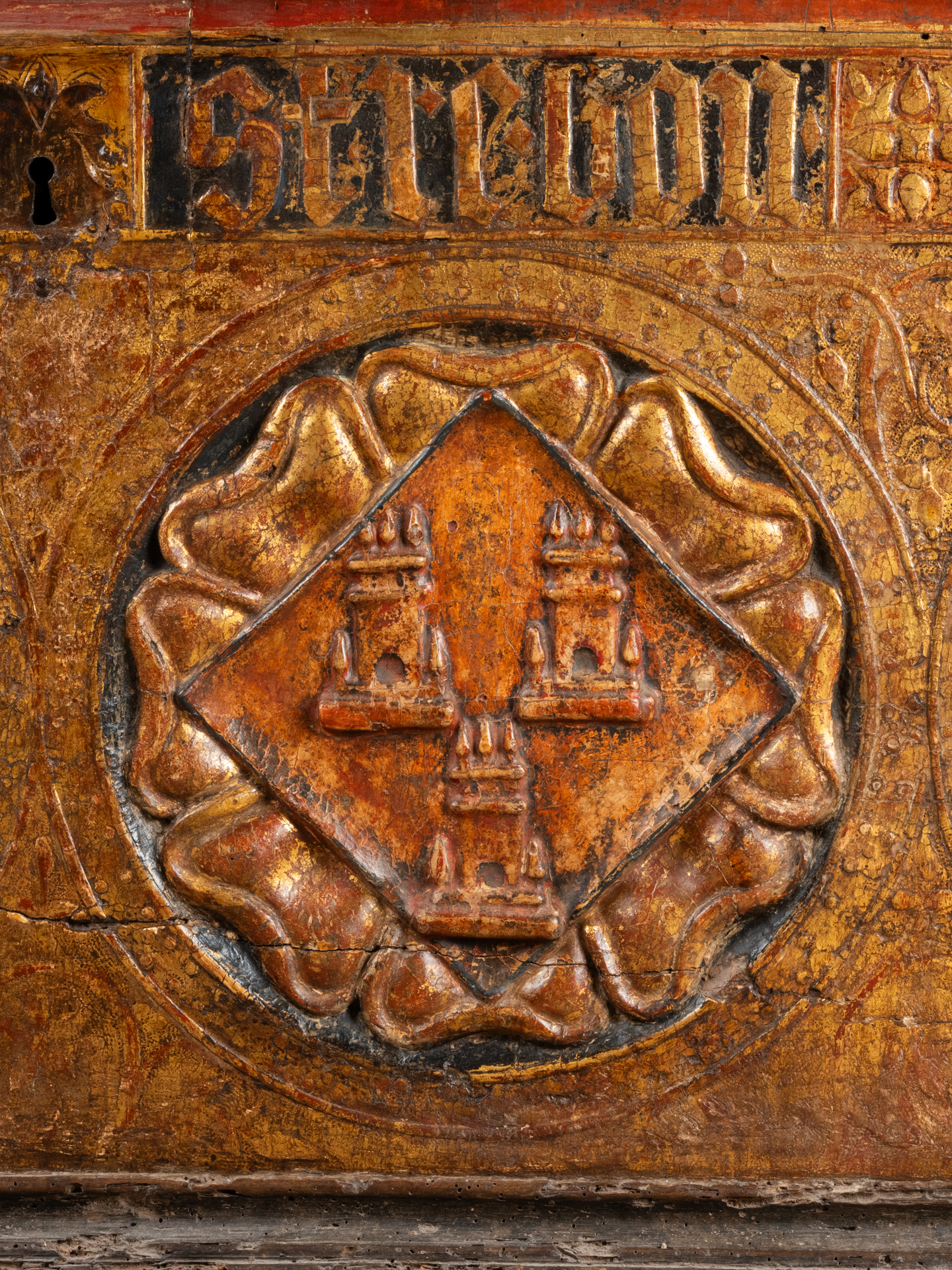

Circular medallions with eight-petaled flower corollas adorn the front and sides, containing alternating diamond-shaped coats of arms with either an inverted key or three towers—heraldic symbols of noble families. A band with a Gothic inscription in French and latin runs along the upper edge, referring explicitly to the wedding day (“le tre bon iorn”) and the sentiment behind the union (“ama y / in tua moi”).

Close comparaisons can be made with a Pastiglia marriage chest on display at the Castello sforzesco in Milan, which present a similar late gothic taste, heraldic decoration and inscription.

The surface is elegantly decorated with a dense pattern of punchwork, creating interconnected vegetal spirals. The interior is colored in black and gold, simulating a starry sky. The repetition of coats of arms underscores the heraldic value of the furniture, likely commissioned for a marriage between two illustrious families that remains unidentified.

The outside is covered in modelled and stippled pastiglia, decorated with free carvings, water-based gild, graffito and tempera polychromy. Pastiglia is the name for a partially pasty, applied mass, usually consisting of chalk mixed with pigments and binders. This technique is mainly used for relief-like highlighting of certain depictions on panel paintings and was already known in Ancient Egypt, where mummy portraits were decorated with pastiglia. Later, this type of relief was also used in the Byzantine area, and from the 12th century onwards in southern Europe, from where the technique of pastiglia spread northwards.

These raised decorations were modeled in gesso on the wooden base with the use of a mold and then gilded. This gesso, made with lime sulphate, was commonly used at the end of the Middle Ages, both in furniture and in the gilded backgrounds of paintings. It was laid in several coats which were burnished in order to give them a soft texture, upon which reliefs (pastiglia) of the same material were added with a flat brush, with a dripping procedure, which were then shaped into a precise form once they were dry.

The pastiglia is modeled smoothly in gentle gradations of relief and painted with colors which accentuated the forms and supplied details of the decoration.

The work is distinguished by the harmonious grace of its composition and the richness of its ornamentation and finishing. The craftsmanship of the embossing in pastiglia, as well as the punching of details and background, is meticulous, creating a vibrant golden surface reminiscent of late Gothic taste. The continuity of the ornamentation recalls the work of embossed, punched, often partially gilded and painted leather, frequently used for furniture and wall coverings. The predominant heraldic theme, as well as the rich engraved decoration on the background, suggests a dating to the first decade of the 15th century. This chest is part of a set sharing the same characteristics, in which figurative scenes are replaced by shields and inscriptions. The most important examples can be found in the collection of the Prince of Liechtenstein (Vaduz), in the Victoria and Albert Museum, in the Thyssen-Bornemisza collection, in the Museo d’Arti Applicate in Milan and in Vienna. Throughout the 15th century, these motifs would give way to Renaissance-inspired designs, including classical figures and ornaments, sometimes combined with painted scenes.

Although it has some cracks and some little loss, its state of conservation is surprisingly good for a piece of this period and decorated with such a delicate technique. It is a very rare exemple of a surviving Cassone that remaining largely unaltered. Cassoni fell out of style even before the Renaissance had ended, and few of them survive intact today. Decorated Cassone fronts were exceptionally desirable on the late nineteenth and early twenty century because collectors highly appreciated their secular subject. Most were dismantled so that their panels could be sold separately on the art market.

Elaborately decorated wooden wedding chests, cassoni, were made in Italy from the fourteenth to the sixteenth centuries and were integral part of the marriage rituals of the elite in renaissance. The word is an anachronism taken from Vasari, the 14th-15th-century term being forziero. Often commissioned by the groom in marriage, a cassone was prominently carried in the nuptial procession, laden with the dowry of his new bride. Wealthy families would proudly display their cassoni as a demonstration of their social standing, further contributing to the chests’ cultural importance.

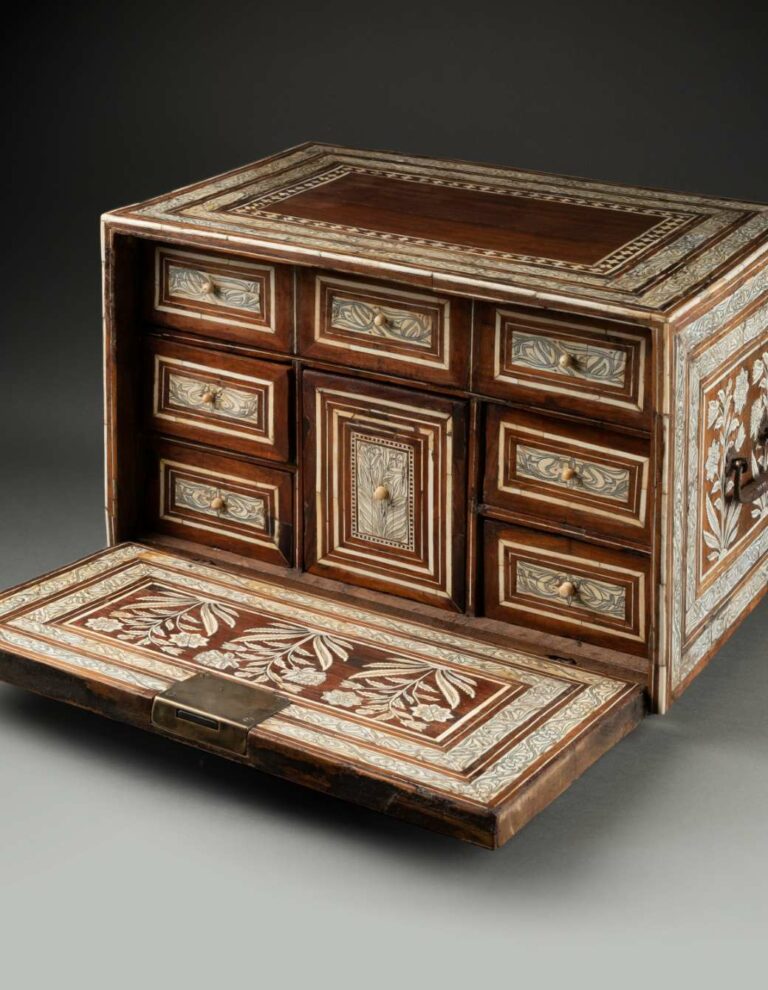

Their function was manifold: to carry the bride’s trousseau to her husband’s house during the wedding parade; to decorate the main bedchamber, often around beds; to encourage, through their pictorial imagery, the success of a marriage and the conception of offspring; to store and keep precious textiles.

In Renaissance Italy, betrothal and marriage were formalized less by written documents, as in our modern world, than by eyewitness testimony of the rituals that accompanied the nuptial process, especially a series of symbolic items exchanged as gifts. The offering and acceptance of such gifts were considered integral parts of the marriage process and could even be used as evidence in legal disputes.

Arranged marriages were the norm. They were regarded as an alliance between two families who were usually of similar economic, social, and political standing. Once a couple got engaged, the bride’s father and her groom negotiated her dowry, which could range from clothing and jewelry to vast estates and other more substantial assets.

Throughout the marriage, the chests continued to be used as storage and seating and were among the most prestigious furnishings in the home.

In an era when homes, even those of the elite, were comparatively sparsely furnished, and when furniture itself was generally quite simple, they would have been the most splendid and distinctive pieces in the newly-weds’ room or camera, a semi-private domestic space which was not only where the couple slept, but was also used for entertaining. They were therefore important vehicles for display, reminders of family alliances and family wealth.

The Renaissance cassone, symbol of the period’s opulence and aesthetic innovation, stands as a testament to the remarkable artistic achievements of the Italian Renaissance. Its exquisite craftsmanship, intricate designs, and cultural significance make it a cherished artifact of this transformative period in history. Beyond its utilitarian function, the cassone serves as a symbol of the Renaissance’s emphasis on beauty, opulence, and the fusion of art and everyday life. Through the artistry of these chests, we gain insight into the enduring legacy of Italian Renaissance culture and its enduring influence on the world of art and design.

Examples of Italian cassoni can be seen in many museums. They form an important source for our understanding of life and society in Italy during the Renaissance and they inform us of important cultural practices pertaining to love and marriage at the time.

Bibliographic references :

- H.Avray Tipping, Italian furniture of the Italian Renaissance as represented at the Victoria and Albert Museum, Country Life March 31st 1917

- Wilhelm von Bode, Italian Renaissance Furniture (originally published as Die Italienischen Hausmöbel der Renaissance, Leipzig 1902), fig. 3; translated by Mary E. Herrick (New York, 1921)

- Borghero, Gertrude: Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection: catalogue of the exhibited works of art. Lugano-Castagnola, Villa Favorita, 1981

- Enrico Colle, Museo d’arti applicate: Mobili e intagli lignei (Milan, 1996)

- Angela Comolli Sordelli, Il Mobile Antico dal XIV al XVII Secolo (Milan, 1967)

- Freuler, Gaudenz (ed.): Manifestatori delle cose miracolose: arte italiana del ‘300 e ‘400 da collezioni in Svizzera e nel Liechtenstein. [Exhib. cat. Villa Favorita]. Lugano-Castagnola, Fundación Thyssen-Bornemisza,

- Patricia Lurati, Doni nuziali del Rinascimento nell collezioni svizzere, (Locarno: Armando Dadò Editore, 2007)

- ‘L’Autunno del Medievo in Umbria – Cofani nuziali in gesso durato e una bottega perugina dimenticata’, a cura di Andrea de Marchi e Matteo Mazzulupi (exhibition catalogue, Galleria Nazionale dell’Umbria), 2019

- Frieda Schottmüller, Furniture and Interior Decoration of the Italian Renaissance (Stuttgart, 1928)

- Schubring, Cassoni; Truhen and Truhenbilder der Italienischen Frürenaissance, ein Beitrag zur Profanmalerei im quattrocento (Leipzig: Karl W. Hiersemann, 1915)

- P.K. Thornton, The Italian Renaissance Interior 1400-1600 (london: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1991)